Women in Contemporary Jewish Thought: A Comparative Study of an Orthodox and a Non-Orthodox Feminist Approach

| Article 6, Volume 3, Issue 6, Summer and Autumn 2014, Page 91-107 PDF (505 K) | |||||||||||

| Document Type: Research Paper | |||||||||||

| Authors | |||||||||||

| Khadijeh Zolqadr | |||||||||||

| PhD Degree in Religious Studies | |||||||||||

| Abstract | |||||||||||

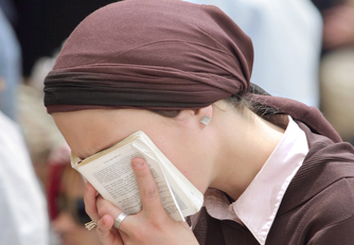

| This paper briefly examines two approaches to the position of women in Judaism. One is from an orthodox perspective, represented by Chana Weisberg, and the other is a non-orthodox and feminist approach, represented by Judith Plaskow. By examining these two approaches, we expect to contribute to a better understanding of the diverse views of women in contemporary Judaism.

Plaskow criticizes the different positions for men and women in Judaism and views them as signs of a woman’s otherness that has resulted from a patriarchal approach on the part of those who authored the scriptures. For Plaskow, the different positions of men and women can only mean a woman’s inferiority. Weisberg on the other hand, acknowledges the different positions of men and women, but argues that these differences are indicators of a woman’s superiority. |

|||||||||||

| Keywords | |||||||||||

| Jewish Orthodox feminism; Jewish non-orthodox feminism; gender differences; women’s otherness; Plaskow; Weisberg | |||||||||||

| Full Text | |||||||||||

Introduction

Like many other traditions and religions today, Judaism faces crucial and essential questions about the position of women in its tradition. These questions come from Jewish and non-Jewish scholars alike. This paper intends to briefly examine two approaches to the position of women in Judaism. One is from an orthodox approach which is represented by Chana Weisberg,[1] and the other is a non-orthodox and feminist approach represented by Judith Plaskow.[2] By examining these two approaches, we hope to contribute to a better understanding of the existing diverse views on women’s issues in contemporary Judaism. These two discourses are on opposite ends of the spectrum of the debate on women’s issues. One end is that of the secular feminist approach in which nothing less than full equality between the genders can be accepted. This would entail accepting complete similarity between men and women regardless of the religious implications that might arise. The other end of the spectrum is the view that is wary of the female nature itself, let alone considering it equal. The views that are explored in this paper are particularly significant because they both claim to speak from within the Jewish tradition, and have been respectful of Judaic principles while also addressing women’s issues as their primary concern. In our attempt to present and examine these approaches, we will mainly examine their understanding of the Torah as the main source of Jewish history. The focus of our attention in this paper is the fundamental question of how women are viewed in the history of Judaism from these two perspectives. Thus, we must address how these two approaches view women in the Torah. What elements have contributed to the different communal and ritual positions of men and women in Jewish tradition and law? From the onset, it should clear that the intention of this paper is not to engage in a discussion about the theological and historical implications of the theories put forth in question, nor is it to investigate their validity based on something like an Islamic perspective. The aim of this paper is to help the reader in viewing these two approaches in their Jewish context and to locate them in contemporary Jewish thought. ۱٫ Woman in the Torah in Weisberg’s ViewWith a midrashic[3] approach, Weisberg portrays women as having a very high position in Jewish thought, to the extent that some women are able to accomplish tasks that men of a high stature would not have been able to accomplish without their assistance.[4] The qualifications that enable women to enjoy such exceptional positions can be followed through Weisberg’s understanding of the creation of woman and of a woman’s spiritual position. ۱٫ ۱٫ The Creation of WomanIn order to fully understand the creation of the first woman (i.e. Eve), we primarily need to understand the creation of man (i.e. Adam). As Weisberg explains, this is because the creation of Eve is the result of a two-phased process: first was the creation of Adam as the first human being, and then, in the second phase of creation, was the appearance of Eve as the first woman.[5] In the process of creating this original man, God took an additional step as opposed to His other creatures. This additional and special step was to begin man’s creation by making an important announcement to the angels: “Let us make man in our form and our likeness” (Gen.1:27). This additional contemplation when it came to man’s creation made this event different and special and underlined the superiority of mankind over all other creations. Furthermore, after man’s physical creation, God Himself blew a living soul into man’s nostrils. Receiving this divine spirit elevated human beings above all other creatures, both physically and spiritually. As a result of this, mankind became capable of appreciating Godliness. It also enabled man to love God, hold to Him, and to yearn for divine experiences. This does not stray far from the mainstream interpretation of Genesis 2 which says that Eve was created from Adam’s rib. However, Weisberg’s interpretation departs from the mainstream view when it comes to Adam’s nature. According to the interpretation that she favors, Adam was an androgynous being that had both male and female characteristics and cannot therefore, as the mainstream interpretation suggests, be a male entity. This being with its unique intellectual, spiritual, and physical qualifications was called Adam by God but was not “male” as we know him today. This unique human being had two sides: one male, and one female. In the next stage of human creation, this being became two separate male and female entities (Weisberg 1996, 26). According to Weisberg’s midrashic approach, this stage was deliberately postponed by God until He had created all creatures and could parade them before Adam. In this way, the first human could assign a name to each of these creatures, and would also have the opportunity to see that all creatures had mates while it did not. In addition to becoming aware that it did not have a soul mate, it perceived its own superiority over other creatures. With Adam having realized these two things, God caused Adam to fall into a deep sleep. He then took flesh from Adam’s rib, formed it into a being called a “woman,” and presented her to Adam who was no longer an androgynous being. He was now a separate male entity with his ideal soul-mate (Eve), a female entity, at his side (Weisberg 1996, 27). As explained by Weisberg, Eve’s creation has several important implications in determining a woman’s position with regards to the discourse in question. First, since men and women are two parts of a whole, they individually constitute half of a being. Therefore, each half needs the other, and must become unified with it in order to be complete. Weisberg elaborates on this implication: Man is unlike all other creatures whose male and female species were created simultaneously and independently. Creatures do not require a mate for the fulfillment of their missions. In contrast, woman was part of a man. The man therefore lacks wholeness without his wife. Only the two together form a complete human being. (Weisberg 1996, 28) Here it seems that Weisberg does not follow her main argument on Adam’s androgynous nature. In the above statement, she acknowledges that the “woman [the wife] was part of a man [the husband].” In a way, she acknowledges that Eve was created at the behest of Adam who was not complete without his wife and who was lonely without her. Regardless of Adam’s nature, androgynous or gendered, it is worthwhile to note that by arguing that it was Adam’s loneliness that caused him to long for a mate, Weisberg has perhaps unwillingly participated in a long traditional and orthodox line of interpretation. Biblical critics have criticized this traditional and orthodox approach because of its failure to acknowledge a woman’s sense of loneliness that is similar to a man’s. Based on the Torah, Weisberg argues that Man, therefore was not only incomplete but he was “not good” as the Torah attests “this is not good, man being alone.” Man is merely a half-person in his original state. God therefore announced His intention to make an eizer kinegdo, a help mate, parallel or on equal footing to him. (Weisberg 1996, 28) Critics say that this interpretation of Genesis 2:18-24 has solely recognized a man’s loneliness and his need to have a helper. It is silent and ignorant of a woman’s need for companionship and her suffering from loneliness.[6] According to them, it does not sound reasonable to admit that a man feels lonely and is in dire need of companionship, while a woman is not. In other words, men and women, who are supposed to connect over a mutual bond towards accomplishing a single objective, are not in mutual need of each other. A man needs a woman as a companion and a helper; however, there is no biblical recognition of a woman receiving the same sentiment from a man. A woman’s exclusion, or at the very least her lack of being mentioned when the idea of companionship is brought up in the verse, does not seem to indicate that a woman is more capable than a man in terms of her ability to cope with loneliness. Nor does it seem to imply that she is created emotionally independent from a man’s companionship and help. She is even put under her husband’s rule (“He shall rule over you” [Genesis 3:18]) for her role in deceiving her husband to eat from the forbidden tree. A woman, who is under the dominion of man, and utterly dependent on her husband, cannot be emotionally independent from him and cannot escape loneliness and incompleteness without him. Weisberg makes use of Adam’s recognition of his loneliness leading to Eve’s creation to indicate that both men and women are dependent on each other. However, it seems that due to the absence of women in the crucial moment of the recognition of loneliness and asking for a mate, a woman’s marginality and her non-essential role is instead greatly emphasized. Second, the creation of women also marks another development in the position women and this is due to her different origin. The first man was created from the soil of the earth, while the first woman was created from a part of a human being who already possessed all attributes of existence. Therefore, we can conclude that a woman is more advanced and developed in her existence and humanity than a man. Weisberg believes that this is what has caused women to mature earlier than men. She also attributes the physical differences between men and women to their different origins (Weisberg 1996, 31). While this argument for a woman’s superior humanity and spirituality has no true Biblical ground, it is also in clear contradiction with Weisberg’s argument that it was an androgynous human, not a man, that was the origin of both men and women. Both men and women would therefore originate from an already existent being and not from the earth. Thus, it is only reasonable to grant men and women equal human qualifications. To be consistent, Weisberg needs to either agree with the equal humanity of both genders (i.e. not the superiority of women) or maintain her fidelity with the text and read it literally, indicating that the first woman was created from a man (this man not being an androgynous being). Third, according to Weisberg, another aspect of the creation of women that placed her well beyond men was the use of the term “built” (wayyiven) in the Torah. This term, related to bina (deeper perception), associates a greater understanding and intuition for women as compared to men (Weisberg 1996, 31). The question that still persists is whether or not this different and advanced terminology associated with the creation of women has led to a different position for women practically and in Jewish laws (halakha). Has it affected practices concerned with the individual and social lives of women or not? These elements contribute to Weisberg’s conclusion that women in Jewish thought do not suffer from an inferior position in creation, but also that her creation is somewhat superior to that of men. However, it should be noted that Weisberg’s account of creation only refers to the first of two passages in Genesis that describe the creation. There is however, another passage (Gen. 1:27-28) that is substantially different and that describes the creation of Adam and Eve as a spontaneous event with no differences in their creation.[7] This passage in Genesis 1 could be considered as evidence for the equality of the creation of men and women in the Torah, which is much more favored by Jewish feminists. However, by ignoring and not even mentioning this account, Weisberg has demonstrated that she is not satisfied with anything less than the superiority of women. She advocates their superiority, not just their equality with men. ۱٫ ۲٫ Women’s SpiritualityAccording to Weisberg, the superiority of women over men is not confined to her creation. She also has a spiritual perfection that places her well above a man’s. It is worthwhile to take a brief look through Weisberg’s lens to see a woman’s spiritual qualifications. However, from the onset, we need to bear in mind that Weisberg is not an anthropologist. Scientific arguments like that of Ashley Montagu’s (1905-1999 CE) that argue for the superiority of women should not be expected in Weisberg’s argument. She relies on a midrashic understanding of the Jewish belief system and on an evaluation of the lives of exemplary and outstanding female figures in Jewish history to arrive at her conclusion that women are spiritually superior to men. She maintains that women have been characteristically endowed with a greater capacity for self-effacement. This qualification expresses itself in several ways, like emuna (faith), mesirat nefesh (self-sacrifice), and bina (deeper perception, intuition). Explaining the relationship between these three and bitul (the negation of one’s sense of self to one’s creator), Weisberg clarifies that when an individual constantly recognizes that God gives them life in every moment, they realize how insignificant they truly are. This awareness enables him to achieve bitul. For such a person, the reality of God and their trust in Him is unshakable. The source of this knowledge is in the soul, in which God is a true reality. Therefore, an individual whose consciousness is constantly connected to their own soul perceives the reality of God. Their awareness is so profound that it cannot be affected by any circumstances and can only be attained through bitul. At this stage, by removing the barrier of self-consciousness, the reality of God becomes as clear and concrete as the physical world is to the person. A person who attains bitul also possesses bina. Such a person is not confined to the limits of their own desires. Further, their perceptions of the inner realities of the world are not affected by their own self-awareness because “the self” and its individualistic outlook are simply non-existent. An individual who has attained bitul, along with the clear perception of the true reality that they have acquired, will be ready to sacrifice their “self” for that reality. Although the life of an individual is the most precious of their possessions, as they advance to the level of bitul, they will willingly sacrifice their life for a higher purpose that is nothing but God (Weisberg 1996, 7-10). Oddly enough, Weisberg does not hesitate to exclusively use male pronouns and nouns like “he” or “man” in describing human spirituality even though she attributes greater spiritualty to women. Weisberg further argues that the superior spirituality of women is reflected in the kabbalah[8] as well. She believes that according to kabbalists, women are physical representations of the final sefirot[9]of malkhut. This representation provides women with all the qualifications of malkhut. Malkhut differs from other sefirot due to the lack of its own distinctive character or attributes. Rather, it unifies other sefirot, harmonizing their diverse attributes before projecting them onto creation. Malkhut does not have any specific attribute or qualification of its own; otherwise it would immediately exclude other attributes. This unique element allows malkhut to encompass all other sefirot within itself and to reflect a more focused light onto creation (Weisberg 1996, 18). To illustrate the relationship between malkhut and women, Weisberg explains that The six sefirot from chesed to yosed represent the six basic directions of the three-dimensional physical universe, north and south, east and west, up and down. They represent the fundamental modes of reaching out to the six directions of creation. These sefirots are referred to as the masculine sefirot because they are directed outward. Malkhut, in contrast, is the axis or focal point at the center of the six directions; instead of being directed outward, malkhut is directed inward and integrates all spiritual illumination. Malkhut is therefore referred to as the feminine sefirot….Just as malkhut has no identity other than the unification of all the sefirot so too, women’s identity is nothing more or less than Godliness. The essential core of a woman has no definition other than a divine one. While men are represented by the various conflicting forces of the sefirot, women, like malkhut, are more unified and intrinsically more focused on their Godly goals. (Weisberg 1996, 17) Interestingly enough, this is the function of the Sabbath as well, which is feminine unlike the other six days of the week (Weisberg 1996, 17). Weisberg asserts that these kabbalistic notions are reflected in the lives of Jewish women. Women, like malkhut and the Sabbath, are capable of integrating all conflicting masculine forces into one unified force, and becoming the channel through which divinity passes into the world. They do not need to confine themselves to performing many mitzvat (commandments). Each mitzvat’s philosophy is to enforce and strengthen the spiritual force in a practicing Jew and to make them sensitive to Godliness. By its nature, the feminine essence is already bound and sensitive to Godliness; thus, it does not require the spiritual influence of certain mitzvat. Men, on the other hand, are obligated to perform some mitzvat that women are exempted from performing, like the mitzvat of tfilin[10], tzitzit,[11] or kipa.[12] This is because men need them to connect their physical bodies to Godliness, to subordinate their desires and reasoning to the divine will, and to subjugate their egos to God (Weisberg 1996, 18). Weisberg elaborates on this notion saying that, “A woman, however, does not require these additional powers from outside sources, as she already possesses them from within” (Weisberg 1996, 19). ۲٫ Women from a Non-Orthodox Jewish Feminist PerspectiveJudith Plaskow, a North American Jewish feminist, who affirms her Jewishness as a central part of her identity has been chosen to represent this trend. She values being a part of a community with its own history, convictions and customs, and holds that they should be preserved. Nevertheless, she believes that these elements should be valued and preserved as elements in dialogue with changing social and historical realities as opposed to a frozen form. She affirms that she feels attached to Jewish history and texts and considers them her own. Therefore, we must view her not as a feminist who turns her back on religious principles in her quest for women’s rights, but rather as a feminist who is determined to maintain her religious identity, while criticizing those elements that she believes should not be a part of the tradition (Plaskow 1990, xiv-xxi). Nevertheless, the credibility of her argument should be examined in light of whether it is committed to the principles of Judaism while it essentially advocates modifications to the main Jewish textual tradition. This section attempts to provide insight into this feminist approach, while also examining such a feasibility. ۲٫ ۱٫ Women’s SilenceThe core of Plaskow’s objection is that which she considers patriarchal in Jewish tradition, which is embodied by the silence and absence of women in Jewish history. Exploring the terrain of the silence of women, she argues that despite the fact that half of Jews have been women, men have always defined normative Judaism. The presence of women and female experiences are largely invisible in Jewish texts and records. In her view, this is especially unfortunate, because like men, women have also lived Jewish lives, experienced Jewish history, and carried its burdens. Nevertheless, female perceptions, experiences and questions have not been addressed in texts which are predominantly records of male activity. In an attempt to explain this, she identifies the key to the cause of female silence within Judaism as being the otherness of women. This notion of otherness is reflected in the following statement by Plaskow: Named by a male community that perceives itself as normative women are part of the Jewish tradition without its sources and structures reflecting our experiences. Women are Jews, but we do not define Jewishness. We live, work, and struggle, but our experiences are not recorded, and what is recorded formulates our experiences in male terms. (Plaskow 1990, 3) She explores this otherness as it appears in central Jewish themes and concerns, i.e. the Torah, Israel, and God, and believes that they are constructed from male perspectives (Plaskow 1990, 3). ۲٫ ۲٫ The Torah and Women’s OthernessLike other feminist theories, like that of feminist theologian Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (b.1938), that insist all religious texts are the product of an androcentric patriarchal culture and history, Plaskow maintains that in the Torah, women are not necessarily absent but rather, they are cast in stories told by men. According to Plaskow, mere female presence in the Torah does not negate their silence. She identifies what she notes as the most striking examples of the silence of women, even in passages where women are central characters. For instance, similar to what was noted in Weisberg’s view, the part that women play in the various familial stories of Genesis is more prominent than that of men. This is to the extent that the matriarchs of Genesis are all strong women; they often seem to have intuitive knowledge of God’s plan for their sons. In fact, it is clear in the stories of Sara and Rebecca that they understand God better than their husbands, who were both prophets of God. However, despite their superiority in understanding God and their keen intuition, these women are not the ones who receive the covenant or who pass on their lineage. Viewing the low-profile presence of women in the narratives of the Torah from a strikingly different perspective than Weisberg, Plaskow does not hesitate to question the very justness of the textual tradition. The great event at Sinai was a significant moment and a turning point in Jewish history. However, Plaskow feels that it was equally important and significant in the establishment of the otherness of women in Judaism. When Moses warns his people to “be ready for the third day” and orders them, “do not go near a woman” (Exodus.19:15), Plaskow’s objection is that when everybody, not just a certain group of individuals, were waiting for God’s presence, Moses addresses the community as men. As a result, at this central moment in Jewish history, women became invisible. Moses’ statement at this crucial time is seen by Plaskow as “a paradigm of the profound injustice” of the Torah itself, through which the otherness of women finds its way into the very center of the Jewish experience (Plaskow 1990, 25). Although she does not solely blame this verse for the situation of women, she nevertheless believes that it sets forth a pattern that occurs repeatedly in Jewish texts. According to Plaskow, the invisibility of women is not confined to this historic moment alone. It is rather reflected in the content and the grammar of the covenant itself, in which the community is addressed through the male heads of households (Plaskow 1990, 25). Plaskow’s concern about the Sinai passage has another dimension, which is that this passage should not simply be considered to be a historic record of an event that occurred long in the past. This event and other important events are not simply historical occurrences, but are active memories that shape Jewish identity and self-understanding. For this very reason, i.e. the significance of the memories of the past and them being part of the Jewish religious identity which has been widely reflected in the works of Jewish scholars, Plaskow suggests that Jewish history should be reclaimed. She finds this task both extremely critical and daunting because, in order to do so, Jewish memories need to be completely reshaped (Buber 1963, 146; Yerushalmi 1982, 9). Plaskow concludes that the Sinai passage, which appears at every Torah reading as a central theme of the Sabbath and holiday liturgy, is a reminder that recreates the past repeatedly. Each time women hear this passage, they hear themselves being cast aside in a conversation among men, or between God and men. Since the covenant is a covenant with all generations, the marginalization of women and their invisibility becomes a theme that one is constantly reminded of. Having discussed the exclusion of women, Plaskow goes as far as to declare, “I call Torah the record of part of the Jewish people because the experience and interpretation found there are for the most part those of men” (Plaskow 1990, 33). Plaskow believes that the silence of women goes even deeper when it finds its way into the language of God. The Torah’s language about divinity is exclusively male. The images used to describe God, who supposedly transcends sexuality, and the qualities that are attributed to Him, all draw on the male person and experience and convey a sense of power and authority that is clearly male.[13] She feels that “[t]he God at the surface of Jewish consciousness is a God with the voice of thunder, a God who as lord and king rules people and leads them into battle, a God who forgives like a father when we turn to him” (Plaskow 1990, 7). On the other hand, she describes the female image in the Bible as follows: “The female images that exist in the Bible and (particularly the mystical) tradition form an underground stream that occasionally reminds us of the inadequacy of our imagery without transforming its overwhelmingly male nature” (Plaskow 1990, 7). Therefore, Plaskow declares that in the Torah, male imagery is proven to be comforting because it is familiar. At the same time however, it is a part of a central system that pushes women to the margins. In an attempt to illustrate the damage that the male imagery of God does to women, Plaskow argues that attributing maleness to God is valuing masculinity. Subsequently, to imagine God as a male is to value the quality of those who have it i.e. maleness, masculinity. Thus, it is very reasonable to place those who share this quality with God in the position of forming the normative community and those who do not share this quality in a marginal role where they gradually become invisible (Plaskow 1990, 7). Nonetheless, Plaskow emphasizes that the silence of women and their invisibility that seems to be prevalent generally in female history, and in Jewish history in particular, does not testify to a lack of historical agency for women. Instead, it illustrates the androcentric bias that shaped history. In other words, similar to Weisberg, Plaskow believes that there were women who played historical roles in Jewish history. However, unlike Weisberg who justifies the quieter and more private role of women as being “behind the scenes,” Plaskow views this as a sign of the otherness of women in the Torah. Plaskow has identified female otherness in Jewish textual tradition including the Torah itself, to be the main challenge facing Jewish women in the tradition. However, she has failed to think of a mechanism that ensures the maintenance of both principle Jewish beliefs and a sense of belonging for Jewish women to the tradition’s history. Plaskow is faced with the pivotal question as to whether or not Judaism would remain if the voices of women were to be heard in addition to the voices of men. This is a fundamental question that is facing many religions (like Islam and Judaism) that claim to encompass the solutions for all human problems, for all of time. This would include issues like gender, plans for prosperity and the salvation of humanity: does religion have the potential to respond to the various needs and questions of their followers or not? To answer such a question, there are a variety of issues that would need to be discussed, including the credibility and soundness of the text and its transmission, the position of the intellect in the belief system, and dynamism of the religious system in light of fixed and variable principles (similar to dynamic ijtihad in Islam). If discussed, these essential issues (which are beyond the scope of this paper), will shed light on various human issues like gender concerns and other questions in religion. It should therefore be noted that Plaskow’s isolated concern with gender issues in Judaism cannot be expected to reach many conclusions without addressing the above. Even if she did address them, it would modify the system so vigorously that it would no longer be the same. ۳٫ Two Feminist ApproachesThese two approaches, albeit unique, have certain significant similarities. This includes the fact that both approaches are committed to maintaining their Jewish bonds. Further, in both approaches, women are viewed as intellectually and spiritually capable of intensifying their relationship with God and attaining spiritual and prophetic abilities similar to and even superior to their male counterparts. Both authors have identified prominent female figures who are known to have achieved very high positions in Jewish history. These theoretical similarities are followed by different practical approaches in determining the role of Jewish women and their presence in religious and communal life. These different approaches come as no surprise as Plaskow and Weisberg have each approached the issue of women in Judaism from different perspectives and with different emphases. Not surprisingly, Plaskow’s argument leans towards equal rights for women in shaping Jewish history, and thus towards their equal right of participation in Jewish religious and communal life today. Weisberg on the other hand, does not deny that the different positions of men and women in Judaism began from different modes of creation and resulted in different commands and rituals. However, she does not see these differences to indicate the inferiority of women; rather, she views them as markers of the superiority of women. These two different approaches have found it necessary to address the differences in the position of men and women in Judaism according to their own terms. They do this by criticizing the differences for their infliction of inferiority on women as Plaskow does, or by justifying it by claiming female superiority as Weisberg does. They have offered different suggestions to addressing these gender issues in Judaism. Plaskow identifies a systematic otherness that has been inflicted on women from the dawn of the tradition and as such, she suggests the rewriting of textual tradition. Weisberg on the other hand, suggests that the female position in the tradition during the pre-messianic era is as it should be, because the world at that point could not contain the thorough godliness of women. Weisberg’s orthodox approach approves the superiority of women in creation and in spiritual and prophetic abilities. However, she does not see this superiority as a justification of female roles as religious leaders or as individuals who receive the covenant. A woman, at the heights of her prophetic and spiritual capabilities, becomes an eizer kinegdo (help mate) for her male partner, who is not necessarily endowed with a higher spiritual and prophetic power (Weisberg 1996, 28). On the other hand, Plaskow does not see this quiet role that women must adopt in the Jewish tradition through Weisberg’s midrashic lens when it comes to leadership or communal rituals. She does not see their silence as the consequence of a higher spiritual power that the world cannot contain. Although she endorses such a power, she does not see female exemption as the result of their spiritual richness. Instead, she calls this quietness, (or as Weisberg might say, this ‘behind-the-scenes’ role of women) as the otherness of women. It is thus fair to state that what differentiates these two perspectives is the way that they approach Jewish theology with relation to its position on women. Weisberg’s orthodox approach reads the theology and accepts it as it is, whilst trying to find justifications for its impact on women by using other sources like the midrash and the kabbalah. By doing so, she persists in her justification of the position of women in normative theology and halakha, and argues that female superiority puts them beyond obligatory rituals and that the world cannot contain their immense spirituality. This perspective leaves Jewish women in a situation where they are exempted from some rituals in the name of superior spirituality, while in reality, these Jewish women do not see it that way. What is the advantage of being superior when it is limited to theoretical implications? For Plaskow, the need to improve the situation of women is real. Therefore, theology and other elements of Jewish thought need to adjust themselves to cater to that need. In this regard, she suggests taking a few essential steps like rewriting history in such a way that women’s voices, experiences, and histories are heard (Plaskow 1990, 7). Second, she suggests changing the theology of the Torah and reshaping it (Plaskow 1990, 22). Third, she suggests modifying a part of the halakha (Jewish law), because it has contributed to the deeper marginalization and silence of women (Plaskow 1990, 26). As mentioned earlier, the changes in different aspects of Jewish thought as advocated by Plaskow, although favored by feminists, would bring about fundamental changes in Judaism through which the maintenance of Jewish principles cannot be guaranteed. In conclusion, these two different positions towards the differences between men and women in Judaism, while different in direction, are strikingly similar in nature; they both have an underlying judgment about the different positions of men and women and seem to have viewed these differences in light of a ranking of their positions as inferior, equal or superior. Plaskow’s feminist outlook promotes the indiscriminate equality of both genders, while Weisberg’s apologetic orthodox approach deters her from questioning, or even inquiring about the differences. She employs midrashic and kabbalistic arguments to prove that these differences are indicators of a woman’s superiority. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that both Weisberg and Plaskow have failed to address possible underlying objectives based on which Judaism has placed men and women in different ritual, legal and communal positions. Regardless of a woman’s superior or inferior position in Judaism, who is to blame for her otherness, and how a woman’s assumed superiority in the spiritual and human realm mirrors itself in the real lives of Jewish women, both Plaskow and Weisberg have overlooked an essential question on gender differences. In other words, their preoccupation with the absolute rejection of different positions for men and women, or their absolute acceptance, has deterred them from attending to the fundamental issue of the gender differences between men and women. They have failed to address the idea that it might be inherently gender that is at the heart of the philosophy behind the different positions of men and women in Judaism. There are also other discourses in Judaism today that do not reject the differences between men and women as Plaskow does, but instead, they value these differences based on the belief that gender differences are divinely willed for a purpose. These differences entail different roles, responsibilities and positions for men and women. This alternative approach does not attempt to identify the inferiority or superiority of either party, and is well reflected in the works of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik[14] as he argues for gender equality but not similarity.[15] Examining the views of Rabbi Soloveitchik with regards to gender is beyond the scope of this paper, but would be helpful in the study of women’s issues in contemporary Judaism.[16] [۱]. Chana Weisberg descends from a long line of distinguished Rabbis. She is a highly sought-after speaker and a best-selling author and columnist. She has served as the Dean of the JRCC’s Institute of Jewish Studies in Toronto, Canada. [۲]. Judith Plaskow is a professor of religious studies at Manhattan College. Her scholarly interests focus on contemporary religious thought with a specialization in feminist theology. Dr. Plaskow has lectured widely on feminist theology in the United States and Europe. She co-founded The Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. She is the past president of the American Academy of Religion. [۳]. The word “Midrash” is based on a Hebrew word that means “interpretation” or “exegesis.” This term, as Jacob Neusner explains, can refer to a particular way of reading and interpreting a biblical verse. It can also refer to a book, a compilation of midrashic teachings or a particular verse and its interpretation. [۴]. For more on midrash and women, see also Bronner (l994, 1-3). [۵]. See Genesis 2: 18-23. [۶]. For more on the arguments of Biblical critics see Hartman (2011). [۷]. Rabbi Soloveitchik has discussed the discrepancies between these two verses and has his own interpretation where he develops his theory of Adam the first, and Adam the second. See Soloveitchik (1992, 10-20). [۸]. he term “kabbalah” is used as a technical name for the system of esoteric theosophy amongst Jews. [۹]. In kabbalistic literature, the sefirot are depicted as emanations or manifestations of God. The concept, colored by Neoplatonism and gnostic thought, was used to explain how a transcendent, inaccessible Godhead (en sof) can relate to the world. In the kabbalah, a distinction is often made between the first three sefirot (regarded as the highest), and the remaining (lower) sefirot. The ten sefirot are the supreme crown, wisdom, intelligence, love, power, beauty, endurance, majesty, foundation, and kingdom. [۱۰]. Tefillin are passages from the Torah that are written on parchment and placed within leather batim (casements), with leather straps attached to the batim. These straps are used to bind the batim and the Torah passages on parchment within them on one’s arm and hand and on one’s head. [۱۱]. The Bible commands the wearing of fringes on the corners of garments (Num. 15:37-41). Initially all garments had fringes; later an undergarment with fringes on the corners was devised for daily use. [۱۲]. This is the skullcap worn by religious Jewish men. The practice of wearing a yarmulke goes back to around the 12th century. It is worn at all times by the orthodox, while the less observant cover their heads for prayer only. [۱۳]. Neusner has the same observation about the masculinity of God in the Torah. See Neusner (1993, 127). [۱۴]. Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903 – 1993) was an American Orthodox rabbi, Talmudist and modern Jewish philosopher. He was a descendant of the Lithuanian Jewish Soloveitchik rabbinic dynasty. He served as an advisor, guide, mentor, and role-model for tens of thousands of Jews, both as a Talmudic scholar and as a religious leader. He is regarded as a seminal figure by Modern Orthodox Judaism. [۱۵]. This is very similar to Shahid Mutahhari’s argument for the equality of men and women but not their similarity. [۱۶]. For more on Rabbi Soloveitchik’s gender views, see Zolghadr (2013). |

|||||||||||

| References | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||